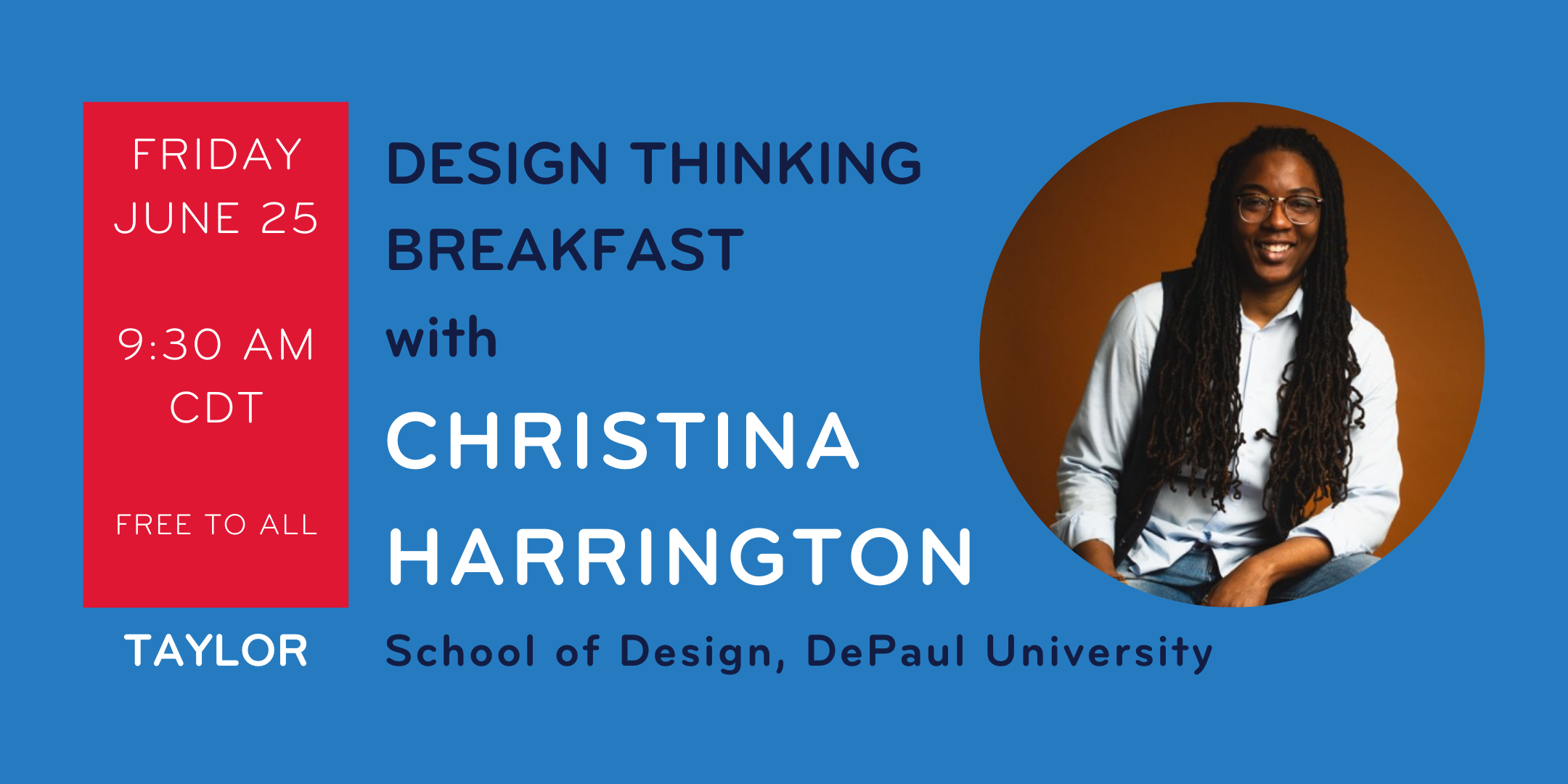

June Design Thinking Breakfast with Christina Harrington

Friday, June 25, 2021

Dr. Christina Harrington led this month’s Casual breakfast series to meet new folks, practice using design, design thinking, other designerly approaches to create social impact.

Presentation Materials

Coming soon!

About the Hosts

While she may be an engineer by trade, Dr. Christina Harrington identifies herself as a designer. She has a background in electrical engineering and industrial design and focuses her design skills and research on the areas of universal, accessible design. Specifically, she has looked at how to use design in the development of assistive products for older adults and individuals with differing abilities, and how to use design to center communities that have been historically been at the margins of mainstream design.

Based out of Chicago, Dr. Harrington is an Assistant Professor in the School of Design at DePaul University and serves as the Director of the Equity and Health Innovations Design Research Lab

Niesha Ford is a second-year graduate student at the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. Niesha works with multiple organizations committed to causes such as: providing services for people experiencing homelessness, encouraging positive racial perspectives, and working with historically marginalized groups to combat the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Video

Transcript

Lavonzell (she,her)|Taylor Ctr

Okay, all right, well, I will go ahead and kick it off. One, I want to welcome everybody I am Lavonzell Nicholson from the Taylor Center for social innovation and design thinking. There, I am the Director of Finance and Operations, managing all of the things behind the curtain. We welcome you to this DT breakfast. The Taylor Center, of course, our mission really is to cultivate change makers and we do that through a variety of things, including design thinking workshops, we have credit bearing courses, we do life design and a host of other researcher, and scholarship in our Center.

This event is part of our dt breakfast series which was started by Leslie, Dr. Leslie Ann Noel who is joining us from Trinidad this morning. And so, this is really about creating a casual space for folks to engage and connect, around design thinking and design thinking principles.

Each month, we have a new person who comes in, and shares their expertise, in the format of a presentation or some sort of workshop and skill building.

Today we welcome Dr. Harrington who is with us today. Niesha will share a little bit about her, and as a quick reminder, this is really about creating community and so we’ll have opportunities for you to connect and ask questions. I will be in the background, just making sure, things are going well and monitoring the chat and supporting everyone as needed.

And I hope you have your coffee and whatever else you need to jazz you up this morning, I have my nice glass of water and without further ado i’ll hand it over to Niesha so she can introduce our presenter.

Thank you so much. So yes, if you’ve been to design thinking breakfast before you know my name is Niesha Ford and i’m the co host. So, i’m not going to do too much introduction about me, I’m just going to get right into introducing our presenter Dr. Harrington.

So while she may be a engineer by trade Dr Christina Harrington identifies herself as a designer she has a background in electrical engineering and industrial design and focuses her design skills and research on the areas of universal, accessible design, specifically she’s looked at how to use design and the development of assistive products for older adults and individuals with differing abilities.

And how to use her design to center communities that have historically been at margins of mainstream design. So without further ado i’m going to turn it over to her to let her also introduce herself and kind of get on with the DT breakfast. Thank you so much for coming.

Good morning, everyone. Niesha could you give me abilty to share screen?

Yeah, go ahead and try now.

So yeah I’m Christina Harrington. I am an assistant professor in the school of design right now at Depaul University, and so I always like to give a little bit of an introduction about myself whenever I come and do these things, because I have a fairly unique background. So, I come from a background in electrical engineering and with a Masters and PhD in industrial design, so I identify as a qualitative design researcher that sits right at the intersection of making things usable and also thinking about the folks who use them.

I like to identify as a SCI-Fi nerd, a DIY crafter, and of course across all of the the spectrum of my work, one of the things that really resonates with my background, that I actually never really thought about being a part of what I do is my love for science fiction novels and SCI Fi tech, particularly that of which is written by black Afro futurist authors, such as Octavia Butler, Kara Keeling, NK Jemison on some of the newer ones,and a lot of work to kind of just centered black people in the existence of the future.

Particularly Octavia Butler’s Blood Child, one of the first ever futurism books I ever read that situated us in the future rather dystopian future, and had us think about well, what does what does it look like for black people to show up in the future of reality and how can that be imagined. And this book was was so critical to my love for science fiction that I can actually still, remember the imagery that I created in my head, even though that this was a purely text based novel. The imagery that I created in my head of you know, some of the depictions that she described and there have been there have been artists, since then

who have come in and created these these imagery.

And we’ve also seen that kind of show up in movies and films and visual albums, yet we haven’t really seen that transfer over to the world of design, by the folks who are actually thinking about in creating and developing the technologies of the future.

Interestingly, when I started off doing the research that I do, as was mentioned in my introduction, I came from a more universal design, accessible design approach or perspective, ,really being concerned with how people use the technologies that they use nd how we can make that better, particularly for older adults and people with disabilities and impairments. And so I kind of found myself in like this human factors and ergonomics area of industrial design.

Mainly because for all intents and purposes, that was one of the only areas that was really thinking about inclusivity in design. And thinking about how we incorporate people that are typically neglected in design into the main streams of design. Doing research in academia, I started off as I mentioned, looking at how do we develop systems, particularly in home assistive technologies, that might support the health and wellness of older adults and one of the things that I kind of started to notice, as kind of like anecdotal data was that we would do these research studies, where we would bring in these older adults and we would say like “hey, you know how well do exercise video games support your ability to like be active in your home?” To exercise, to do yoga Tai Chi, to just get up and moving, because we know the benefits of that we know what the statistics say. In terms of, being more active supports longer life, lessened chronic disease and all of these things.

But when we would bring in the samples, and a lot of this research was done when I was living in Atlanta Georgia as a PhD student at Georgia Tech. We would bring in these samples of older adults and even balancing them for race, one of the things that I would notice is that, among some of the more affluent white older adults living in, Buckhead or even some rural areas,that had a higher social economic status would say things like you know, “I think that this would be an amazing technology for me to get active i’m going to go out and buy it today.”

“My grandchild has one of those i’m going to start playing it with him” or you know :my daughter has one or we can have this in our living room”, whereas alot of the black older adults, that we would have come in and do these studies will say things like Similarly, “I think this will be a great technology for me to get up and get active, but I can’t afford this.” We you know we might be able to get one device in the entire building. So this was great, thank you for allowing me to come in for this study but it’s not really going to you know impact my daily life in the immediate because it’s just not attainable.

So I then kind of shifted my research to to solely focus on how can we consider lived experiences.

Christina Harrington: of marginalized individuals and by marginalized I define that as those who have been historically oppressed, particularly within the context of the United States, so those who have been oppressed by race, age, gender representation and sexuality, income and class, ability, disability and how can we think about centering those intersections of those identities, within the design that we’re doing. You know, how can we move from just saying you know we’re designing for older adults to realizing that designing for older adults is not a monolith. That all older adults do not have the ability to attain the same things, and so my work became purely focused on designing for black and brown communities and the intersection of what that meant for ability, disability, and impairments.

And so, one of the things that you know was really interesting I actually attended a, a human computer interaction consortium, several years ago, where one of the keynote speakers gave this prompt of “can we consider science fiction of the past as bringing about innovation of the future and the ways that we’re thinking about the future of technology?” Can we, you know, kind of lean on the science fiction that we grew up with as being that that will kind of you know, particularly potentially speculate what technology of the future will look like?

During this presentation, there were images of Star Trek and Star Wars and the Jetsons, Back to the Future and I’m sitting in this audience and i’m thinking to myself: I don’t see on screen or any of the images that I remember reading about in the science fiction, that I was interested in growing up with right.

And so, this kind of brings me to this notion that I was in wonderfully post, and this was actually a billboard that was posted in East Liberty and Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, the kind of situation that you know, there are black people in the future. This billboard actually stood as a protest in a movement kind of a call to action for a lot of the redevelopment that was happening in the Pittsburgh area for folks to think about. Sorry, for folks to think about you know how do we include the black and brown communities that are currently being displaced, in the ways that we’re thinking about the revitalization of cities right, because we know that that oftentimes doesn’t happen.

Many of you have shared like where you’re calling in from and a lot of these cities we’re seeing the same gentrification efforts happening we’re seeing people come in developers come into neighborhoods that we’ve historically lived in as black and brown communities and realize them as potential economic areas of new development without really considering the needs of the communities that are already there.

So this kind of bridges me to thinking about well you know how are we thinking about the black people in the future of design and the black people in the future of technology.And it most closely resonates with one of the things that Anthony Walton posed in the late 1990s in his essay of Technology versus African Americans. Where he talks about that most of the technology that is actually consumed by Black Americans does not include Black Americans as the architects, as the developers, of those technologies, despite the prevalence of how much we use it. And the potential of the impact that it would have on our everyday lives.

When we fast forward to today, we see that you know from the 1990s up through 2021, this is still a little bit of an issue or or a major issue, with the contrast of representation of you know how black and Brown, so the Spanish, LatinX folks how this lack of representation that we see in the design field right now. The 2016 design census show that 7% of those in the workforce and the design workforce right now we’re Hispanic with 3% being bBlack.

And why does this lack of representation matter? Well when we think about what happens when we’re not in the room, a lot of folks may have heard this kind of metaphor of a seat at the table and being in the room, and things like that, when we’re not in the room, we have technologies that are designed not only what does not in mind, but also technologies that actually become harmful and can target certain groups. So, similarly to the a lot of the research that I did early on thinking about how everyday technologies might not meet the needs of all older adults, we now see that technologies such as facial recognition, you know search algorithms, surveillance technologies, are actually quite harmful and they target black and brown individuals.

Because we have very little say and inclusion in these tech spaces. And this is because, historically, the area of human computer interaction and design has not really focused on issues of race and ethnicity. Things like system bias, lack of equity, and access or who has access to a technology have not really been considered in the ways that we come up with these these systems. So one of the first questions that I wanted to pose, and just kind of have a little bit of a conversation for a couple of minutes are what are some examples of systems or technology that exclude marginalized groups? For those, with those identities. I’d like to kind of give them the stage first ,what are some systems that you feel like, have directly excluded you in your everyday life and why? We could have a little bit of a conversation.

Pulse pulse oximeter , yeah, definitely.

And for those who aren’t familiar pulse oximeter there’s been a lot of research showing how they actually do not accurately read on, the skin of people of color, and this became something that was a big topic of conversation with COVID, pulse oximeters are supposed to be one of the ways that you can read your oxygen to let you know, you know if you need to go to the hospital, what are your oxygen levels. If it’s telling me that my oxygen levels are fine, because it doesn’t accurately read my skin, it actually becomes you know, a potential health risk.

Are we considering financial tools like mortgages and technologies and guys? Please feel free to turn on audio, I don’t want to misinterpret anyone’s comments or questions, as Lesley Ann mentioned, this is really informal so.

I was, I was thinking about the steep V analysis, a lot of futurists use it is sometimes a lot of designers tried to bring it to the space, and I was like that needs to be redesigned, that’s harmful.

Anyone else?

I’m going to jump on because I have to jump off in a few minutes but i’ve been like over the last let’s say three years i’ve been trying to buy a home and have been personally been able to see okay how, like not being a traditional land owner or you know I’m not American so that I have passport issues, and you know all of these systems, financial systems, will exclude somebody like me because I’m not American you know because I don’t have a long enough financial history, and you know. Actually, I am in a place of privilege because I’m a university professor, but I’m excluded. So what about other people who have even less access than me.

Mhmmm,,

Applicant tracking systems used an HR Does anyone want to expand on that i’m not familiar.

Leslie Coney

And yes, I haven’t had this experience, personally, but I have talked to people, who have or even HR managers like noticing certain schools not passing like a applicant tracking systems either take a job application or like your resume or something and screen through those types of processes. And I’ve heard of instances where like certain universities were flagged as less than or even trying to look at someone’s name on that may not look or sound familiar, and those names are generally like Black American or LatinX, so that was basically what I was speaking to us.

Okay cool.

We had um I just want to point out, we had someone asked Could you elaborate elaborate on steep V and then we have one other thing about contraception technology to kind of saw that.

So I don’t know who mentioned this Steep V. Would you mind elaborating for us?

Oh yeah that was for me.

I think I spoke, Steep V is like an analysis tool i’ve seen a lot of futurists use it, but it’s really grounded they’re like foresight, like business tools and analysis tools and I find it quite harmful, using it within design space because of the limitations. And it’s only like to me, I feel like it’s like only certain people can kind of look at it. And it’s a superior like tool, that only people who can see through these eyes can actually utilize it, so I think is like quite harmful bringing it into the design space without it being like critically looked at.

Thank you.

I’ll turn it back over to you Dr. Harrington. I was just trying to make sure everybody’s points in there.

No worries no worries. I mean somewhat so similarly, in the same vein, a lot of what I’ve also considered is, you know how we portray black and brown individuals in the design work that we do oftentimes we’re when we think about working with black and brown communities and design, it’s almost framed as like the outreach sector of design. The community outreach you know how do we bring these populations up to essentially white standards typically framed around some type of deficit or disparity. Centralizing whiteness as a norm and a standard and other rising anything that is not that how many of you are familiar with the acronym of WERID.

So white industrialized educated rich. Does anyone remember what that D stands for ?

Is a developed?

Perhaps developed, but it essentially says that most of our design and technology development is centered around those samples, those groups, those populations and that, when we think about who we’re designing for and that’s the methods that we use and the access that we’re really thinking about when we’re designing technologies, it centers around kind of that acronym of that population. And one of the things that I’ve done is really tried to challenge that by expanding technology access.

To saying you know will What if we actually think about technology accesses being more than just physical and sensory accessibility, but actually addressing those other identities outside of that weird acronym.

So what if we actually think about technology access as addressing economic viability right. When we’re proposing solutions in a particular demographic context, are we doing so, such that people can afford it, and it can be able to be maintained within the context of deployment long after you know the product is developed. Are we thinking about the cultural relevance and the impact that a technology has with a particular group? Does it resonate with people coming from different lived experiences and backgrounds. Oftentimes even within the context of the United States, we have people that are are coming here, living from other countries, are we making products accessible. To be inclusive of people that might not speak English as a first language or are we saying hey you need to acclimate to this norm, this standard of English as being the basis of everything and ignoring the fact that these groups that for the longest time have been considered a minority have actually we’ve become the population majority. Yet in design, we’re still kind of siloed right.

And so, I’m thinking about a more equitable and inclusive design framework. And so I have another discussion question, I realize I’m still in the other mode, that I want to get to and kind of explaining where i’m coming from with this, a lot of the research that I do I kind of merge interaction design and this area of health and racial equity.

Such that we’re thinking about these things, and the technologies and the systems and even the spaces, or the the the Community environments that we create right because design is really expansive design is not just a physical thing that you hold or touch right. Design also speaks to a way of thinking, design speaks to policy, design speaks to, as we talked about that neighborhood revitalization. And so, a lot of the work that I’ve done in the past, working at this intersection of a more equitable and inclusive approach to design and accessibility has allowed people to have input, direct input into the ways that we’re thinking about design and the world around them. Whether it be for health and wellness technologies, whether it be the ways that we think about community spaces.

Whether it be you know, looking at how technology allows us to interact with each other. And a lot of this work has allowed me to also kind of you know, open up this thought of: how do, how do we allow design itself to be more inclusive such that groups that are typically neglected or and are typically excluded from this process are actually feel as though they have ownership of what design, is what design could be and how they could use design?

So a lot of the work I do leans heavily on participatory methods for those who aren’t familiar with participatory design essentially says that we are situating the people that are most impacted by the thing or the outcome of design within the process of design itself, so when we go in and you know, we identify what the scope of the project is we’re including people in that. When we identify what methods and what approaches we’re going to use we incorporate people in that. When we actually go through the process of brainstorming coming up with ideas, we’re finding those ideas ,were incorporating people in that. So a lot of the research I’ve done over the years, has really worked to see how can we make design itself more inclusive such that groups, you know that are have not always been included feel like they have more of a say and, and this has primarily been done with black older adults and lower income neighborhoods.

Looking at supporting health and wellness more holistically. And finding things like you know engaging in this form of design, can actually start to promote community activism and health activism such that people you know, are taking ownership of what’s happening in their own communities. Such that people are saying “hey we don’t have to just deal with the standards of you know what’s been the case here, for as long as we can remember that we have problems with”. We’re actually going to come together and collectively identify ways to change these things. But this doesn’t come without faults right. And so a lot of what I’ve been having conversations with people like Lesley Ann and and I see Woodrow is on the call and some other folks is you know when we think about merging this area of you know more equitable inclusive design and traditional design thinking it kind of hits a head. Where there are these tensions. And there are these tensions, because some of the traditional ways that we approach design might not be well accepted by groups that have been historically oppressed. For example, things like blue sky ideation. So I’ve done design workshops, where people will comment on how this concept of blue sky ideation can actually be infantilizing or unrealistic.

And for those who aren’t familiar blue sky ideation is one of those design techniques, where we really urge people to think about the wildest, craziest, blue sky idea that you possibly can.

You may have heard you know in workshops people say things like “money is no constraint” “resources are no constraint” come up with the craziest idea that you can because we want to see how that can lead to something feasible in the scope of what we’re brainstorming. But one of the things that I found was that doing that type of ideation with groups where money is a constraint, resources are constraint, actually became really frustrated. Because they were like this is unrealistic. I don’t want to sit here and spend my time thinking about you know strapping a rocket ship to my back and saying that that’s the way i’m going to get to the doctor and brainstorming about that, because you know i’m actually trying to get to the doctor in the immediate and having a more realistic solution would be a better use of my time and what we’re doing here.

So how do we ground inclusive participatory design in the immediate. You know, still thinking about the distant future, of what we’re creating, but how do we ground it such that that those futures kind of connect and make for more of a realistic experience, based on the expectations of the folks that were working with And in that instance it brought me to some of the other tensions of things like you know co-design or participatory design and many of these instances is oftentimes too late. We’re oftentimes coming behind and trying to address things that have been challenges for so long that again, that blue sky ideation is not going to lead to you know, what community residents, or the groups that we’re working with really want to focus on.

And then lastly, a lot of the times, there is a long standing history of you know, long standing tension between a lot of the the communities, and you know local industries. Local academic institutions, and so, how are we thinking about that and being mindful of that, when we’re going into these communities to try to do co-design work. You know, are we thinking about the history of the institution with the community itself.

So this kind of brings me to you know kind of looking at well what are really the goals and the intended outcomes of participatory design or typical design thinking co-design versus taking a more community based approach? And in a lot of instances participatory design the goals are predefined by the design team. We’ve sat, you know, as an industry team and said here’s what we want to come out of this. And oftentimes it then makes that co-design exercise really just validation of what we already wanted to do.

And in most typically we see here that designers are so much more focused on the outcome of the design than the process or, then the people that they’re impacting, that in reality that participatory part of that design kind of starts to fade into the background.

Whereas thinking about you know community based participatory approaches to design, we see that the goals are more community driven. We see that we’re we’re situated folks directly at the center of what we want to happen and how we want it to happen therefore becomes more participatory action-oriented. where you know we’re actually taking action with the communities that we’re working with and we’re then focusing on how we disseminate the things that we’re doing, and not just what the outcome of that thing would be.

So a lot of the work i’ve been doing leans heavily on making this process more equitable, thinking about how we can be more inclusive with these populations, and kind of bridging participatory design, with more community based approaches to design with the the values of you know, we’re considering the resources that people have, were considering the outcomes that they want to have and what that timeline looks like. We’re considering featuring directly from the perspectives of the folks who want these things to happen, and it can shape the direction, and the trajectory of the project itself. You know, we may not be defining the next wearable tracker, because people might not want another wearable tracker right. If we take steps back and say how do we better scope what the project is itself, we might fint that people want, you know more public displays of health information or youb know or those, I saw a couple of people that are chiming in from Raliegh. And I know Lesley Ann is familair with Raleigh. One of the really cool things I saw when I lived in Raleigh was like the walking index be actually displayed on public signage right maybe the the the outcomes that community wants is is much lower fidelity much you know lower in technical terms, but it’s still giving us the same type of information.

And we’re coming to see the value of integrating black and brown communities directly into the ways that we think about community futures and technology futures. So with things like box ville and 51 futures, if anyone is calling in from Chicago or is familiar with my brother Chris Read, he is a faculty at the Illinois Institute of technology and has kind of really been the architect of a lot of what they’ve been doing with 51 futures and thinking about the future, you know what does equity look like in the Brownsville corridor and the Southside corridor, what does anti racism. look like in Chicago and allowing the community to define that themselves through activities that have been directly integrated into Box ville, which is, I believe, a weekly or bi weekly pop up in the south side of Chicago. We’re also seeing that with like the pack project by Stephanie Dinkins where we’re talking about the future of AI.

You know we’re seeing how these community lead and community driven initiatives are actually serving to really incorporate voices of black and brown communities in the design of things right and thinking about, you know how do black and brown communities see themselves in the future. So it doesn’t have to just be defined by you know the the the science fiction that came from yesteryear, but we can actually think about this and an architect this for ourselves, so one of the next, the discussion questions I wanted to float around, you know from the perspectives of practitioners, I don’t know if we have students on the call, you know what are the ways that we can better include marginalized groups in the design process and envisioning the futures of their their communities?

I know, for me, as a practitioner and I’m always a student but as a practitioner as well um one thing I do i’ve opened up my, how I look at the design process, not as something that is like linear I open it up to be more like life, giving or life cycles and one thing that I do that, like the first step, even before I come into the community I hold space with them. I’m not there to like dictate anything, I’m listening to language understanding their values, how they use phrases, how they commune together. I’m listening to their issues and problems and I’m also hearing solutions to them, Like they have their solutions. As a designer I’m there just to facilitate the process and to amplify or galvanized the things that’s needed and get them to a specific place.

Hey hey as a student and practitioner. We spend a lot of time really going to where people are when we’re working with young people to be able to, you know, spend time with community organizations meet with young people, you know it’s summer in Chicago it’s fraught sometimes, how can we make sure these young people can join us at a space that safe for them and make their parents feel good about it, so we spend a lot of time on the phone with parents, caregivers, aunties, to make sure they’re young ones are going to be good, and we pay them and we have food, and we do all the things that we’re just described is to create a space, and I think one of the things that.

I spend the time I spent a lot of time with a lot of human centered designers and who are doing client based work and in the temporality I just think needs to be different like these engagements that relationship to time is different, and you have to you have to make more space and more time to do good work and work well.So I’m not a big fan of the sprint you know build a cohorts and some time we have a Youth Council now we spend a whole year with and I think that’s so important this isn’t just a Saturday workshop, this is a bit along the long conversation of change and how how we can support our young people in creating these pictures of them

Okay.

Susie Beltran-Grimm

I think oh, this is Lucy, as I said, I similarly to Kessa, I hope i’m not butchering your name i’m so sorry if I am. I’m saying as a practitioner student, I think I just finished my data collection for my co-design co-creation project with Latino families and one of the things that I was trying to really do was just to listen and make sure to view them from an asset based perspective, instead of being worried about been my mat know what are the rules of the principles to co- design and one of the things that I noticed is that alot of them assumed they were not creative.

And it was really interested to see how they assume that creating designing things are only meant for creative people and that they were like are we supposed to do this workshop? And there it was really a process for me to sort of build that confidence of them like I have even one participant, one mom texted me said that she was so scared she’s going to be looked down by her peers or their parents like as not as smart enough, which I think it kind of gets what Christian was saying about who can be creative and who owns the space and they really didn’t see themselves that way, and so it would just be like what pieces so like I just make sure that I keep listening, kind of helping build that confidence and facilitating the process instead of sort of having expectations and just kind of let it flow and obviously provide all the tools needed for them to feel that they can be creative too.

Yeah, and also just to add to that one of the things I know, that I know we have we’re wrapping up soon, and one of the things that I wanted to share that we’ve been doing is also really considering how do we use our position as design faculty, design practitioners design, you know, however, you identify design strategist to really amplify community needs, and community wants and community desires, as opposed to defining them. You know, when we think about the trajectory of like what where participatory design came in, as opposed to just designing for community. We’re designing with a community and one of the things i’m really kind of pushing towards is how do we relinquish power to allow communities to really have ownership of that design. And so we’ve been thinking about like you know what are toolkits and resources that we can create as designers and what if our role as designers is just to you know, take the input that we’re getting in our and our engagements with the community and then creating toolkits, creating resources that allow folks to go through these design exercises on their own and create their own design process.

So we’ve been working with some community partners, black queer women lead feminist centered community collectives and designing an Afro futurism speculative design toolkit.

For those who aren’t familiar ever futurism is a concept that was coined in the 90s. Where it’s centers both the lived experiences, the social, political engagements and the black aesthetic in the ways that we think about the future.And Afro futurism as a design lens was really introduced by Woodrow Winchester who’s on this call today, and you know kind of presents a more inclusive way of thinking about design of which you know this whole thing i’ve been talking about this entire time, black and brown communities are seeing themselves in the future. And we’ve seen Afro futurism, as I mentioned, I grew up reading some of these books. You’ve seen it in literature, we’re seeing it more media with things like black panther and comic books and we’re seeing it popping up in visual albums and album covers.

But where we have yet to really see this kind of sprout and take wings is in the field of design and design thinking and in the ways that we’re thinking about designing future technologies or products or systems.

Woodrow and I have had conversations where we’ve been like you know what we’re kind of pull a really good portfolio example of someone using Afro futurism to design a thing and it’s just not really out there yet. And for me it’s it kind of raises this question of if we’re thinking about science fiction and forming the futures of technology and the future, has this been you know, become an area that’s been neglected, and how can we expand this so, the Afro futurism speculative design tool kit that we’ve been working on is is one approach that we’re taking to doing just that and having people walk through design engagements where they are kind of centering principles and tenents of Afro futurism thinking about liberation and thinking about freedom.

Directly from the perspective of the black lived experience or as Andre Brock calls it, the black ethos. And thinking about topics that you know impact black and brown communities, but not just those that are deficit based and disparities based right. So thinking about concepts like environmental racism, but also thinking about concepts like community building and honoring our ancestors, and you know, amplifying on you know our culture and our heritage and our lineage.

And doing this through an approach of design. Similarly we’ve also i’ve also been thinking about you know how do we put our resources that you know inform people about you know the value of using design as a catalyst for change with things like the Denison Designer project Xen, that we are making, like we have made publicly available for folks who just want to say how do I think about using design, in the context of some of the community building and some of the community change that I want to see.

Some of the things that I want to have implemented and, again, not necessarily focused on technology, not necessarily focus on a tangible thing, but maybe we’re talking about changing the ways that people interact in our neighborhood maybe we’re talking about you know changing traffic patterns, to make our neighborhood safer. How do we use design to think about those things directly, you know from a grassroots level of coming up with it, by the people who live in these neighborhoods as once Winchester mentioned, you know slowly over talk yesterday this “for us by us” concept, and I think when we think about the future of design thinking, you know, one of the things that i’ve really been preaching everywhere, I can, if anyone, you know keeps up with the any of the stuff that I do i’ve been talking about this concept of collectivism and why collectivism is so so so important because collectivism is kind of, the foundation, and the basis of how we engage with each other as human beings, so if we’re thinking about this this essence of collectivism and design, how do we allow the folks that have these these communal relationships to define what design looks like in the concept of their neighborhoods.

So I just wanted to leave kind of with this concept of or this question of you know what is collectivism to you how are you implementing this, if anything, or what are your ideas for how you can implement this and working with the communities that you’re working with or thinking about the work that you’re doing in your area of design?

I know for me, I started like when I was in grad school, which I just got out of grad school but, you know, i am a forever student. Um, I started creating my own tools to understand because I saw like as a designer I have to i’m like i’m really sensitive to context, because I am i’m choosing to be a designer um and so because of that, my values have to align somewhat with the people that i’m working with or it won’t work. And so one of the tools to activate it was I was using wooden symbols to whenever I was working with the client or a community partner and not a client my apologies, a community partner. We would go through, and we talked a little bit, and I was like okay with choose a value, I wouldn’t tell them what it was, it was just, they were just wooden images and they have the African symbol as well as the word and then they would turn them over.

I would turn on mine over and then we would kind of engage one another, like oh wow you think this and I think that and it kind of opened up the space, a little bit to say like okay we’re centering ourselves and we’re grounding ourselves moving for on how we’re choosing to engage in doing the work, and I felt it also grounded them that I was there and I will be there for them always and not, I will try to offer a change, who they are, but I will support them in the process, while we’re designing together. And so I think you know, creating tools that allow us to bridge versus break because a lot of these a lot of design tools that we’ve been taught, especially went from a research lens they break their breaking technologies.

Mhmm, mhmm. Anyone else?

It looks like we have a hand up from Kathleen.

Kathleen Agaton (she/her)

Yes, hi everyone.

Thank you so much for this space, I guess i’ll just share that so I don’t know what I call myself but um I work for a homeless Services Agency in New York City and lead up like research evaluation and strategic learning and we’re really trying to embed human centered design and in our services I’m really trying to evolve that and I just want to share that we’re really informed by principles around trauma informed care. Like we’re trying to weave these things together, the principles of human centered design, libertarian design and trauma informed care, and I think the principle around collaboration, maybe speaks to your question about collectivism.

We’re not only struggling to figure out, you know how to really get meaningful engagement or participation with our clients, but also our staff right. Being trauma informed about our staff who are on the front lines, and you know essential workers and large and many of which are also, the majority of which are from marginalized communities ourselves so we’re just throwing that out there that’s another space to explore to is people delivering the work to and and how it needs to just really be part of our culture and organization.

Alongside being able to do that really well with clients. This idea of thinking collectively and problem solving together so it’s got to be on a couple of different levels.

Yeah I think what’s been interesting um the trauma informed care and trauma informed- I’ve seen this these discussions start to pop up around design. One of the things that, a point of conversation that i’ve been having with focuses, what does it mean, specifically in the context of designing with or for black and brown communities to just center you know everyday existence and things like joy. To your point things like liberation, things like rest, things like peace.

You know I liken it to if anyone has seen that meme that talks about how Issa Ray is one of the few content creators that is creating media where black people are just existing. There’s no trauma porn, there’s no racist antagonist that we’re running from, we’re just showing up, breaking up with our boyfriends, cheating, you know going to work hating our jobs, trying to find a good coffee shop, or you know um and I literally mirror that to design. Because I’m like where is that sector of design for black and brown folks. Every time we talked about, and a lot of these these these paradigms that exists assets based design, value sensitive design, trauma informed design, they all center us needing something.

In a way, that someone is like coming to save us or help us and it’s like hey What if we just wanted to to design something purely off the basis of me, you know wanting to enjoy my Saturday. Whereas the App that says, I you know where’s where’s the City Finder App that just shows me where the cool things to do are. Right? Oftentimes we’re creating those things for ourselves. We’re creating the Apps that you know, introduce us to a neighborhood or a city companies have yet to see value in that.

And so I think for those who are working in industry that’s one of the things that I would really push you to consider. As I mentioned before, when you’re thinking about black and brown communities, is your natural bias, to go to them being some type of outreach? Something that you need to fix or save or help, you know, focus on the because, ultimately, even.

I think my point is even in like things like trauma informed design you’re still, we’re still saying that there’s something wrong. And that becomes really uncomfortable and it spills over into so many different areas. I can’t even tell you how many panels i’ve been asked to speak on about my experiences being black in X that are really just asking me to talk about how I don’t fit in or what is the trauma that I’ve experienced.

Instead of this, where I get to come and talk about my work. So when we’re thinking about new paradigms and new frameworks, I like things like equity centered design, I like things like libratory design, but I want to push that further to say, can we just design almost like you know really leaning on Adrian Marie Browns like Emergent Strategy and Pleasure activism where it’s just purely for our existence, and not as resistance not, as you know, we’re fighting you know white supremacy and patriarchy because yeah we are, we know that, and we know that’s you know part of it, but also just like us just existing I don’t know how to better explain that.

Now that was that was awesome and that’s a fairly strong point to leave off on i’m sorry that we are at time, but if anyone wants to continue this conversation I did drop Dr Harrington’s Linkedin in the chat. Also feel free to sign up for our next DT breakfast which will be in July, but I just want to thank you, Dr Harrington for coming.This was a really interesting talk and like I said very powerful notes to leave off on yeah I just want to thank everybody for coming, thank you so much, and enjoy your weekends.

Thank you.

Thank you so much.

About Design Thinking Breakfast

- Design Thinking Breakfast is a series of casual events that will be moving to an online format until further notice … and breakfasts will be BYOC – ‘Bring your own coffee’.

- The goal is to learn from each other. The format will evolve as we learn, together, what might be most valuable (and enjoyable!) to us all. Breakfasts will include both time to mingle and one or two quick activities to foster knowledge-sharing or community-building.

- The DT breakfasts are open to all. No DT experience is required.

- Come with an open heart and mind and prepare to learn and share with others in the local, regional, and international DT community.

- Please invite anyone who would enjoy both sharing with and learning from other practitioners and educators in the greater New Orleans area, the Gulf South, and connecting with other people in the local, regional and international design thinking community.

- When: One Friday each month.

- Cost: Free

- Contact: nford@tulane.edu