Art Museums and Social Change with Megan Flattley

Hello again! Megan Flattley, 2020-2021 Taylor Center Research and Scholarship Graduate Assistant and art historian here, in my previous blog posts I introduced my own research on art and social change, as well as the possible intersections between Social Innovation and Community-Engaged Scholarship. This time I have some thoughts on where social innovation overlaps/could overlap with my own academic discipline. While artists have long created socially-engaged work, and as such art historians have studied the social impact of artistic practice, today there are particularly exciting conversations happening around the role of the art museum in generating social change.

Fine Arts Museums

When you think of a fine arts museum you might be picturing a large, imposing, neoclassical building with white walls and a security guard that whispers “shh” if you are making too much noise.

Above: photos of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

This common view of art museums (that is perhaps reinforced by pop culture depictions – “Bueller…Bueller…”) can be a barrier to visitors who don’t have art history-based cultural capital, that is, those who might not feel comfortable discussing art or feel that they know much about it. Art museums can also be overwhelming in their sheer size and scope – the collections in encyclopedic museums, like our own NOMA, were built to be “universal.” However, the decision of what gets collected has always been informed by who is in power and what narratives they want to tell. For this reason, museums can be imposing to visitors who don’t feel represented within them. In the United States, the largest art museums were founded through the wealth of families such as the Guggenheim, the Rockefeller, and the Whitney and museum boards are likewise comprised of incredibly wealthy individuals today. Current protests at MoMA and other museums are demanding change in the makeup of museum boards and demanding that those who made their wealth, for example, in the sale of opioids like the Sackler family, not serve on museum boards or have their names on galleries.

Despite these elite connotations and their origins in colonialism, art museums today are a unique public space that can serve as a site of dialogue. The notion of the museum as a utopian space where visitors can leave radically transformed has its roots in the very origin of the museum. Studies have shown that museums rank among the most trusted public institutions worldwide and thus offer space where debate and conflict should be encouraged as functions of civil society.[1] Practitioners today are increasingly exploring the ways in which museums can serve as sites of democracy and how they can serve the community in which they exist.

Artists for Social Change

While we have seen immense growth in the literature on art and social change in the last twenty years, this is not a new idea. As I mentioned in my previous blog post, artists of the early twentieth-century avant-gardes believed that their art had the power to build new worlds. A contemporary practice that has seemingly inherited the mantel of these artist movements is called Social Practice Art (Check out Professor Adrian Anagnost’s seminar on Social Practice Art on offer in the Fall!) This phenomenon describes artistic practice that has moved outside the studio into the realm of communities and politics (though the idea that art was every separable from these things is debatable). Artistic director of the public arts organization Creative Time, Nato Thompson, defines Social Practice Art as “cultural practices” that “indicate a new social order – ways of life that emphasize participation, challenge power, and span disciplines ranging from urban planning and community work to theater and the visual arts.”[2]

The fluidity of this definition mirrors the fluidity of such practices, which can include long-term education initiatives, social movements, as well as community art and civic centers. From an artistic perspective, Social Practice Art emerges from a tradition of participatory and performance-based practices. More immediately, Social Practice emerges from the tradition of Relational Aesthetics which Nicholas Bourriaud termed the artistic works of the 1990s that were about “learning to inhabit the world in a better way, instead of trying to construct it based on a preconceived idea of historical evolution.”[3] Claire Bishop calls it a practice that “aims to restore and realize a communal, collective space of shared social engagement.”[4] Thus, one of the key aspects of Social Practice Art is the notion that people and social issues are the material for artistic creation.

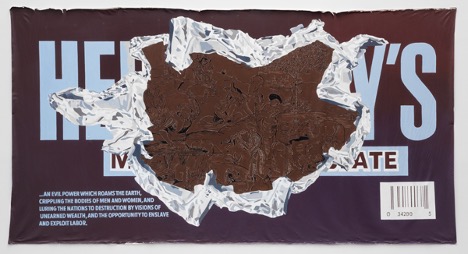

Examples of Social Practice Art include Cuban artist Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International project that was developed with the Queens Museum of Art in 2011 to create a community space where artists, social service organizations and others could discuss immigration reform. Mexican artist Minerva Cuevas runs a web-based nonprofit called Mejor Vida Corp (“Better Life Corp.”) that distributes resources such as pre-paid subway tickets, barcodes to reduce the price of produce, and student ID cards to receive reduced rates at museums. This aspect of Cuevas’ practice is in addition to her more traditional artistic work that also critiques capitalism as an economic system.

[1]Museums Association (UK). 2013. ‘Public perceptions of – and attitudes to – the purposes of museums in society’. Available at: https://www.museumsassociation.org/news/03042013-public-attitudes-researchpublished

[2] Nato Thompson (ed.), Living as Form: Socially-Engaged Art from 1991-2011, (New York: Creative Time; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012): 19.

[3] Nicholas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics. Trans. By Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods. (Les Presses du réel, 1998): 13.

[4] Claire Bishop, “Participation and Spectacle: Where are We Now?” in Thompson, 2012. P.36

Above: Minerva Cuevas, Bitter-Sweet Hershey’s, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 85×160 inches.

There has been criticism of SPA projects such as that of Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates, who rehabilitates buildings on the South side of Chicago and turns them into arts and culture centers. Critics have warned that these artistic works contribute to the gentrification of neighborhoods or that they use funding that could otherwise go towards other avenues of social change. The field of Social Practice Art is a very exciting site for debate around the role of the arts in social movements today.

Social Change and the Museum

One of the questions that Social Practice Art raises for the field of museum studies is how to display such work that looks, and fundamentally is, different from the paintings and sculptures we are used to seeing as art. I have seen innovative museum practices applied by Tulane’s own Newcomb Art Museum. As a student curator I worked on an SPA exhibition titled “Culture, Community, and Civic Imagination in Greater San Juan,” that was part of a larger show called Beyond the Canvas: Contemporary Art from Puerto Rico. To curate this exhibition, the students of the class “Women, Community, and the Arts in Latin America” (taught by Dr. Edie Wolfe) had to consider how best to present in a museum artistic and social practices that were maybe not meant to be displayed as such.

Above: Installation photos of “Culture, Community, and Civic Imagination in Greater San Juan” at the Newcomb Art Museum, on display April 26-July 9, 2017.

In a similar manner to which Social Practice Art embraces collaboration, many museums are exploring new models of coproduction in exhibitions as a way to increase engagement, tell new stories, and acknowledge the interdependence of the museum and those who visit it. I was able to work as a Curatorial Research Assistant on the NAM exhibition Per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana. This is where the majority of my thinking on museums and social change developed. Per(Sister) was created in partnership with two formerly incarcerated women and organizers, Dolfinette Martin and Syrita Steib. The exhibition presented the personal and intimate stories, in their own voices, of 30 formerly-incarcerated women. The exhibition could not have been made without the expertise, generosity, and continued involvement of these community members. Per(Sister) demonstrated that the sharing of decision-making power can open the possibility of collaborative activism and meaningful community building both within and outside the museum.

Above: Installation photos of Per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana, Newcomb Art Museum, on display January 19-July 6, 2019.

I explored some of the meaningful practices developed in Per(Sister) and how they might constitute a practice of “Curating for Social Justice” in a forthcoming article that will appear in the Journal of Curatorial Studies in the Fall. I argue that museum practitioners should collaborate with community members and organizations in their pursuit of social change to ensure the creation of exhibitions that reflect multiple voices and experiences. We are lucky to have a museum on campus that is exploring and developing these innovative museum practices – check out their current exhibition Laura Anderson Barbata: Transcommunality.