Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design

On January 10, 2017, the Tulane City Center was re-dedicated as the Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design. The Center was founded in 2005 and has completed over 85 projects with countless students, faculty, and community partners in the city of New Orleans. Through their generosity, Albert and Tina Small have made it possible for us to continue to connect with students and engage with the community in the work of collaborative design. Included below are some of the remarks that were made at the dedication ceremony:

Kenneth Schwartz, Dean of Tulane School of Architecture

We are gathered here today not only to celebrate the many successes of the former Tulane City Center, but to begin a new era of community engagement and solutions-oriented partnerships as the Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design. For over a decade, the Tulane City Center has developed a flexible, nimble approach to the unique design challenges—and overwhelming potential—that the city of New Orleans presents. Again and again, we have successfully provided the community with dynamic solutions that regard the distinctive nature of the city as a source of opportunity, one that offers our students and faculty at the School of Architecture and the staff of the Center a chance to perform collaborative design work that helps our city’s neighborhoods to thrive.

And every step of the way, Sonny and Tina Small have been our most ardent supporters and devoted friends. Today, I am excited to celebrate this new chapter for the organization as the Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design. I look forward to building upon our exceptional history of thoughtful design research, interdisciplinary dialogue, and targeted built work at this critical moment for our city.

Chesley McCarty, student

I recently had the honor of serving as a fellow here at the Small Center. This past summer was full of learning lessons and reality checks, and of difficult conversations that I wasn’t used to confronting. I had just completed my fourth year in architecture school, and for a moment there I thought I had it all figured out. I had studied abroad, I worked on the URBANbuild house, I had completed all of my community service requirements and more. The record would show that I was on track to enter the architecture field with the tool kit I would need to engage critically with the client, the community, the end user, and for the most part, things were shaping out alright.

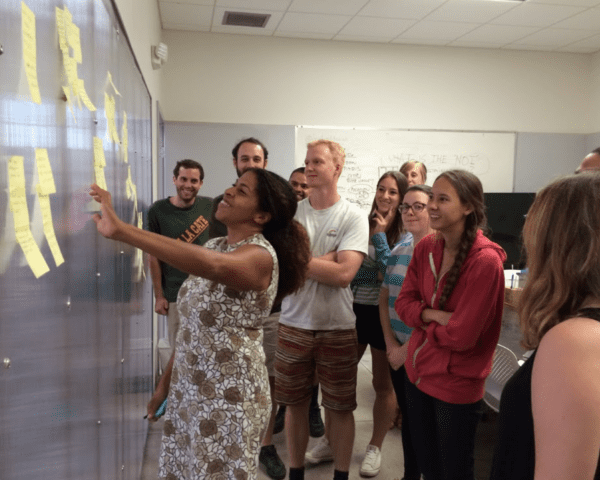

During the first week of the fellowship, we each attended a conference at the University of Virginia called “Design Futures,” a conference on “public interest design” that entailed a week of seminars and discussion groups on how the built environment has perpetuated problems of race, gender, economic and social inequality. We critically engaged these topics with strangers and peers in ways that I had not yet done before back on the uptown campus, and we dove deeply into questions about privilege and discrimination. This conference and these conversations set the stage for how much of the summer would unfold.

Shortly after the conference, I wrote a blog post titled “Redesigning A Design Education,” as both a reflection and a manifesto for myself, my colleagues, and my very limited readership. I was critical of the blame that was so quickly directed towards the built environment – what about the developers? the clients? The politics of it all? But I knew that as an architecture student and budding designer, I needed to own up to my privilege, education, and my knowledge to ensure that the future of design was a more inclusive and collaborative practice. In order to do this, I proposed two approaches. The first involves actively engaging the end user group directly and consistently throughout the design and implementation process, leading to a collective consensus on the ultimate design. This, as I learned throughout the summer while working with a local non-profit organization to develop some brochures on the affordable housing crisis in New Orleans, is far easier said than done – it requires patience, humility, and very strong active listening skills. The second approach, and perhaps the one that I find myself leaning on more as I look beyond graduation, is that in order to really see some of these radical changes that are necessary for the built environment to become a healthier and more inclusive place, we cannot only engage the community; we must also engage developers, the patrons, the policy makers, the business owners, or better yet, we have to become them.

As we begin to think about how we can prepare many disciplines to address both our ethical and carbon footprint, it is time that we seek a change in our education, and places like the Small Center serve as a model for trans-disciplinary education. Here, an amazing team is preparing young designers to see that the built environment is at the forefront of many issues we grapple with each day – issues of shelter and affordable housing, sexual orientation, maintenance of tradition and heritage, education, health care – and they are showing that students do have the power to change these things, but only when they accept that their role as an architect is larger, or actually perhaps smaller, than what they might have learned in the classroom.

My fellowship last summer shaped my understanding of architecture and my future as a designer. I learned that I can use my design degree to become a consultant, a politician, and sociologist, a developer; in fact, the very essence of a public interest designer demands that my architecture hat be one of many hats that I own and wear consistently. I am grateful to Sonny and Tina Small for investing in this education and collaboration, and for not only providing a space where a new form of education and architectural discourse can take shape, but for helping to empower students and give them the tools that they need to become engaged citizens, creatives, listeners, thinkers, and designers. With the work and approach of the Small Center and similar projects beginning to take hold around the country, and with so many students choosing to work with the Small Center throughout their tenure at Tulane and to allow lessons here to infiltrate their work, practice, and values, I am excited to see what the future of design and the next layer of the built environment will look like.

Maggie Hansen, Director of Sonny and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design

Thank you all for being here today. I’m so glad to celebrate with so many friends, allies, and collaborators – locally and nationally. And I am grateful to the Small family for their generosity. Over the past eleven years, the Smalls have seen the Tulane City Center grow into what we are today, and we thank them for their advice, dedication and support along the way, and now, into a long future.

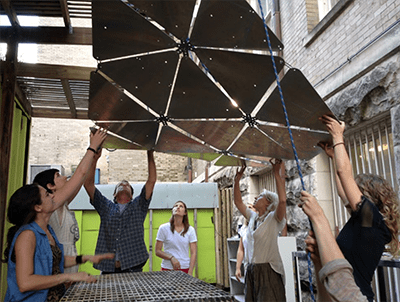

Since its beginning, Tulane City Center has used a nimble approach to addressing complex problems with good design. We bring together the expertise of Tulane School of Architecture faculty, student, our staff, a wide range of experts, and the knowledge and expertise of engaged community members and in collaboration these teams advance community-driven ideas. Our work has been as small as a simple neighborhood map that encourages people to explore the local flavors of Bayou Road, and as large as a neighborhood planning process, often evolving over many years, with layers of complexity.

Our work is developed from strong partnerships with organizations that are deeply rooted in their community. When we are at our best, these true partnerships result in designs that celebrate the specific local context and the exceptional people who live and work here. True collaboration takes time to develop trust, to push past niceties – we bring our role as designer but also our role as friend and neighbor. These are lasting relationships, and we recognize that continued partnership is critical to chipping away at the larger systemic issues that we are all grappling with. Our partnership continues after construction concludes; we are here to take the calls when there is a problem with the building, or a client wants us in city hall to help plead a case, or there is a wedding, a birth, or a crawfish boil.

Our students experience how one small change in the city’s fabric can catalyze change of larger systems, and they see that good designers are also good citizens. And we are excited that students like Chesley represent the next generation of design leaders, who step up to the challenge of working with humility and openness to new models of practice.

We are excited to build on the rich history of collaborative work and to push ourselves further. In the years ahead, we will continue to engage local youth programs, build the field of public interest design and encourage a more diverse pipeline of young designers to enter the field and improve our world. The Small Center for Collaborative Design has the capacity to not only change New Orleans, but to contribute to long-term positive change by bringing together design and civic engagement.